In a move that has sparked widespread concern among democracy advocates across West Africa, the Togolese parliament has approved sweeping constitutional reforms that effectively abolish presidential elections and hand sweeping new powers to an unelected executive position.

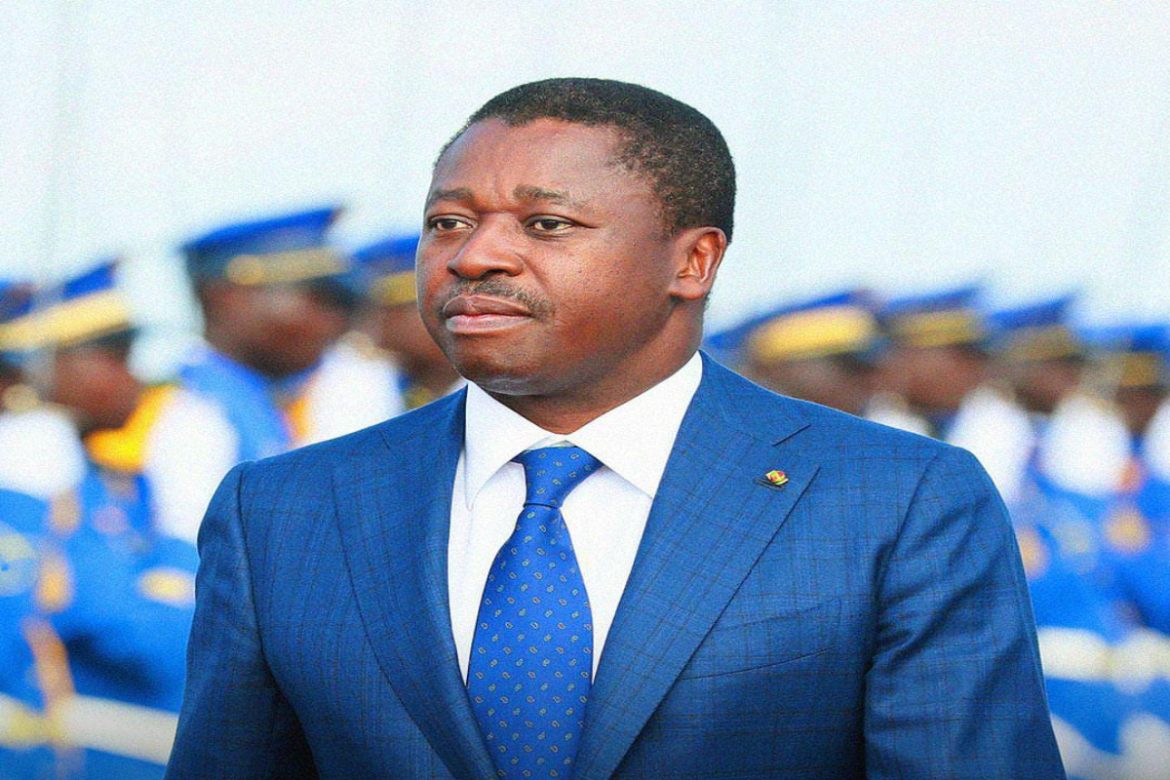

That role President of the Council of Ministers is now occupied by Faure Gnassingbé, the very man who has ruled Togo for nearly two decades and is the son of the country’s former long-time autocrat. The change, passed into law this week, marks one of the most dramatic shifts in governance in West Africa in recent years.

Critics say it’s a “presidency by another name.”

This is not reform its reinvention of authoritarianism, said Dr. Issa Tcham, a Togolese political analyst based in Accra. “What we’re seeing is a complete erasure of electoral accountability.

Under the revised constitution, the presidency becomes largely ceremonial, and the real power now resides with the Council of Ministers a body controlled by its president, who will be appointed by parliament rather than elected by the people.

Faure Gnassingbé, who has already served four presidential terms since 2005, was sworn in this week as the council’s first president.

The implications are vast: there are no term limits for this new role. And since the president is chosen by lawmakers not voters Togo has effectively ended popular presidential elections.

The Gnassingbé family’s political dynasty is one of the longest in Africa.

Faure’s father, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, seized power in a military coup in 1967 and held it until his death in 2005. Faure, then a relatively unknown political figure, assumed office shortly thereafter in an election widely criticized for irregularities.

Between father and son, the Gnassingbés have now held power in Togo for 57 years longer than any single ruling family in modern African history.

Togo’s move echoes a broader trend in the region. In the past decade, countries like Côte d’Ivoire, Rwanda, Uganda, and Congo-Brazzaville have altered constitutions to extend presidential terms. Elsewhere, countries like Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Niger have faced coups driven by dissatisfaction with leadership.

What we’re seeing is a rollback of democratic progress across West Africa, said Olumide Ajayi, a governance expert at the African Centre for Strategic Studies. “Elections are becoming optional or cosmetic.

The African Union and ECOWAS have yet to issue strong condemnations of Togo’s reforms, but civil society groups say silence will only embolden other leaders contemplating similar power grabs.

In Nigeria, where public trust in electoral processes is fragile but still alive, analysts say Togo serves as a cautionary tale.

We may complain about INEC and vote-rigging,” said Abuja-based policy analyst Abiola Sanni, “but at least we still have elections. In Togo, people now have no say at all. That should alarm every African citizen.

International reaction to Togo’s constitutional changes has been muted, overshadowed by crises in Sudan, Gaza, and Ukraine. But for Togolese citizens, the change feels personal.

Many young people over 60% of Togo’s population is under 25 see little hope for democratic change in their lifetime.

I was born under Gnassingbé. My father was born under Gnassingbé,” one university student in Lomé told CNN on condition of anonymity. “Now it seems my children will grow up under them too.

Togo’s story is not just about one man or one country. It’s about how fragile democracy remains in parts of the world where power still bends institutions, not the other way around.

As global attention shifts and fatigue grows over democratic backsliding, Togo may not make front-page headlines. But its transformation offers a case study in how autocracies adapt quietly, legally, and effectively.

And unless there’s collective pushback from within and outside it may not be the last.